The International Criminal Court (ICC) is facing a generational change in leadership. In December this year, the ICC Assembly of States Parties (ASP) will elect six new judges, as well as a new prosecutor, at a moment in which the court has increasingly fallen target to external attacks. In this context, committed and capable judges are crucial to the court’s future. The Assembly elects six judges every three years from a list of candidates nominated by states parties. This year, states have nominated 22 candidates for six open positions.

The Open Society Justice Initiative has been monitoring these nominations closely. In its 2019 report Raising the Bar: Improving the Nomination and Election of Judges to the International Criminal Court, the Justice Initiative highlighted several flaws in the law and practice governing judicial appointments at the ICC. Deficient judicial appointments negatively affect the overall quality of bench. The report ultimately concludes – among other findings – that most states do not select judicial nominees through fair, transparent, and merit-based procedures. This means that most states fail to adequately assess candidates’ skills and qualifications before putting them forward. The risk is high – this can lead to nomination of candidates that are unqualified to serve as ICC judges.

According to the Rome Statute, states can nominate candidates using the process for appointment of judges to the highest domestic courts or to the International Court of Justice (ICJ). Raising the Bar found that states often use neither of these processes and that, even when they do, the processes often lack merit-based selection. When it comes to the actual election, states parties also often cast their votes based on considerations other than merit, such as exchanges of votes with the nominating country for a similar favor at another institution.

A 2019 ASP resolution [pdf] encourages states to “submit information and commentary on their […] nomination and selection procedures to the [ASP Secretariat and to the Advisory Committee on Nominations (ACN)].” While only four nominating states submitted or agreed to make this information publicly available, the Justice Initiative collected additional relevant information by directly reaching out to most nominating states, by carrying out its own open-source research into national legislations and practice (when applicable), and by making use of its existing research for Raising the Bar. Following the closing of the 2020 nomination period on May 14, 2020, the Justice Initiative assessed the processes followed by the 22 states that nominated candidates.

National Nomination Procedures

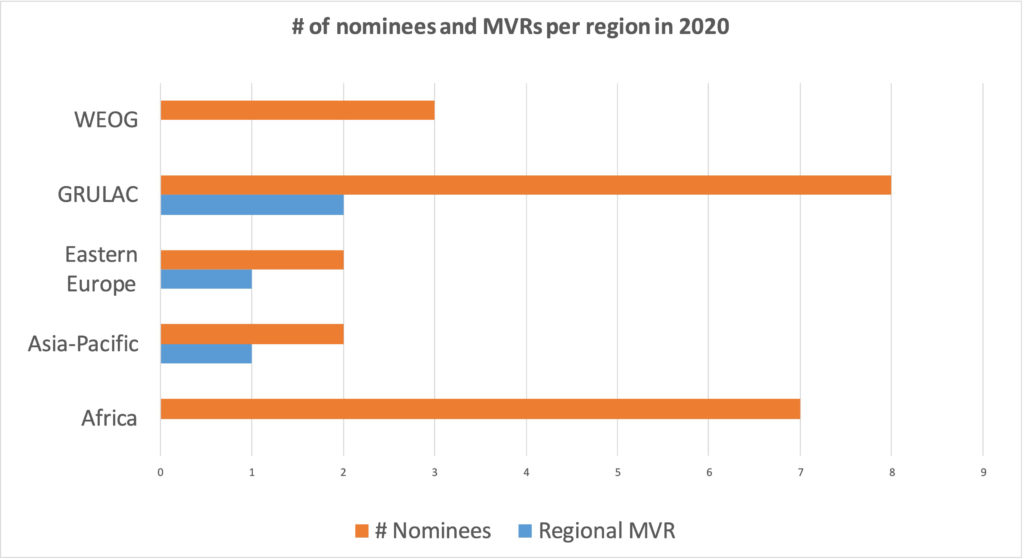

While the ICC does not set quotas for gender, geographical, and expertise-based representation, the Rome Statute and the ASP [pdf] have established minimum voting requirements (MVRs) as a way to ensure adequate representation in these areas.

Of the 22 candidates put forth by states parties:

- Seven are from the Africa regional group: Burkina Faso, Gambia, Nigeria, Republic of Congo, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Tunisia;

- Two are from Asia-Pacific states: Bangladesh, Mongolia;

- Two are from Eastern Europe regional group: Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia;

- Eight are from the Group of Latin American and Caribbean states (GRULAC): Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Mexico, Trinidad and Tobago, Uruguay;

- Three are from Western European and Other states (WEOG): Belgium, Greece, United Kingdom.

- Nine are female candidates, and 13 are male candidates;

- Fourteen candidates were nominated under List A, and eight were nominated under List B.

Several states nominated candidates without providing information on the nomination process that led to the candidates’ selection. While most states did indicate whether their nominee was selected in accordance with the process for appointment of judges to the highest domestic courts or to the ICJ (as they are required to do under Article 36(4) of the Rome Statute), only four actually described the procedure they followed. Only a minority communicated whether their selection was carried out in accordance with a pre-established legal framework, whether they held an open call for applications, or whether an independent body evaluated candidates’ skills in a fair, transparent, and merit-based manner. Several states appear to have conflated the requirement to indicate the procedure used for nominations with that of describing and commenting on how that procedure was carried out. For example, they simply stated that their nominee was appointed through an existing national process used for appointment of national judges without providing information on if and how the position was advertised, whether interviews, exams or other assessments were conducted, or describing the decision-making process and other steps that led to the candidate’s nomination.

The Justice Initiative has nevertheless gathered information on how most countries arrived at their nominations by directly reaching out to diplomatic delegations and by conducting its own research.

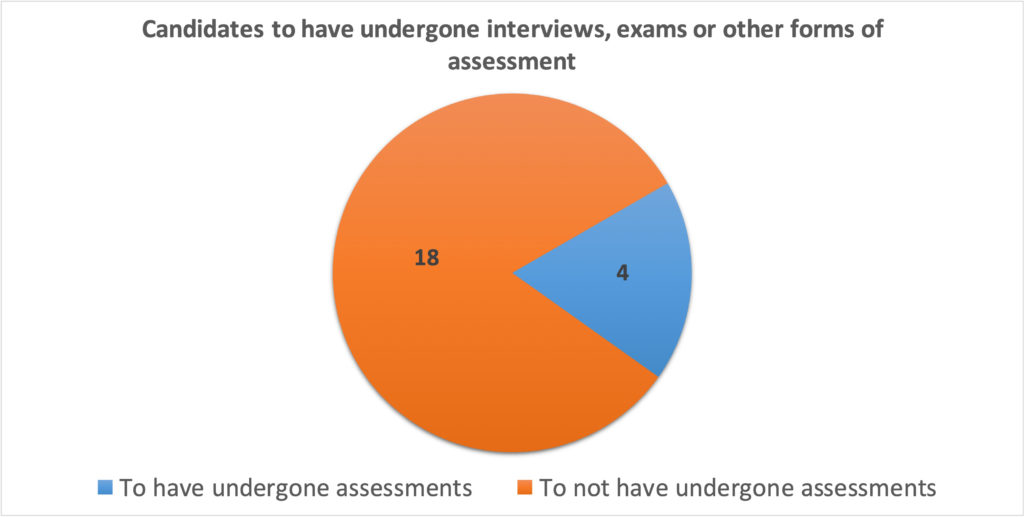

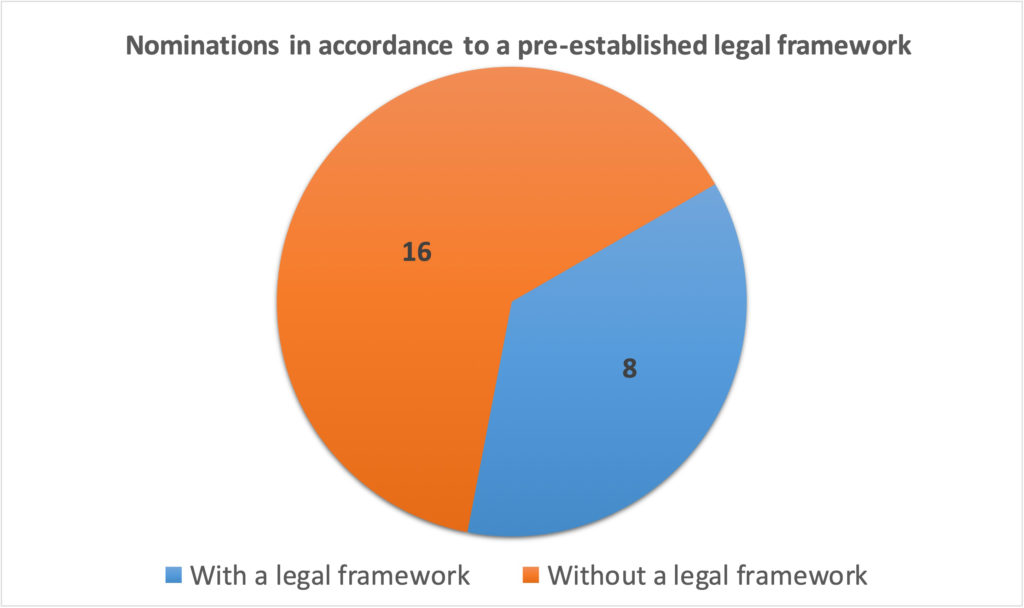

We are concerned that the weaknesses we identified in Raising the Bar persisted through the procedures that led to the 2020 nominations. Fair, transparent, and merit-based processes continue to be rare. We found that eight of the 22 nominating states applied a pre-established nominating procedure, while only four candidates underwent an evaluation that consisted of either an interview, an exam, or a hearing. Similarly, only six states parties carried out open calls for applications. Our research identified only seven instances in which an independent, non-executive body played a role in assessing candidates’ competencies and experience.

It should be noted that one nominating state purposefully adopted a legal framework for ICC judicial nominations in advance of their 2020 nomination.

Overview of Nominating States

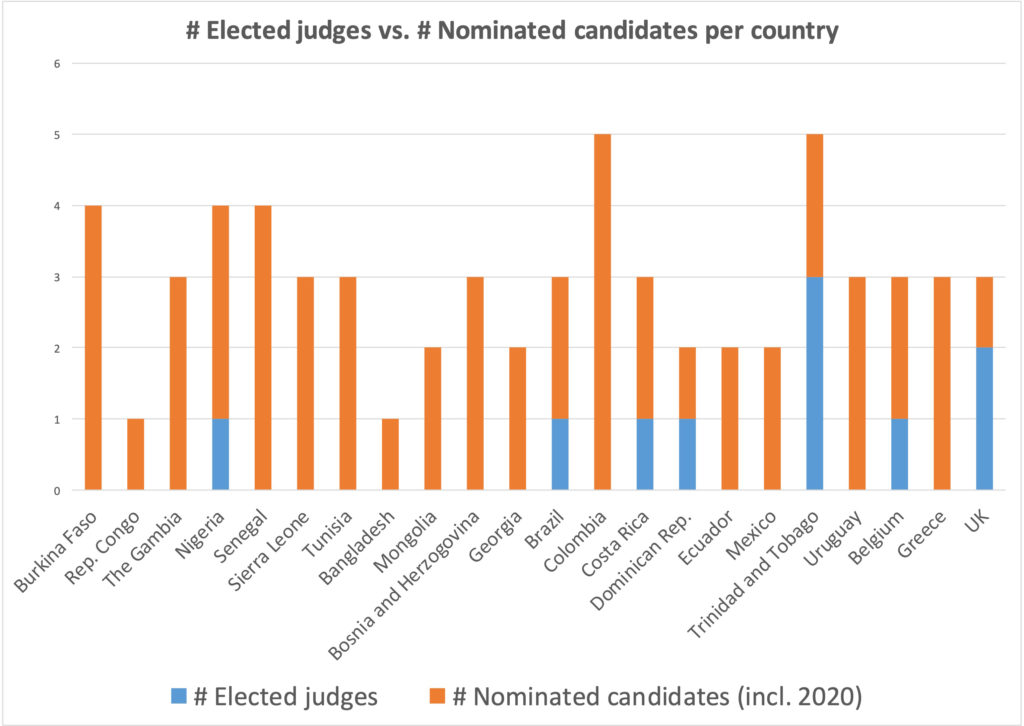

In Raising the Bar, the Justice Initiative found an alarming concentration of the ICC’s judiciary in only a handful of states, as well as a historical lack of engagement of most states parties in the judicial selection process.

The trend continues. In this year’s election, only two countries (Bangladesh and the Republic of Congo) nominated candidates for the first time, while 15 countries had already previously nominated at least two candidates each. Two of those are nominating for the fifth time (Colombia and Trinidad and Tobago). Of this year’s nominating states, 15 have never successfully elected a judge to the ICC, and two states are pursuing their third successful election (Trinidad and Tobago and the United Kingdom).

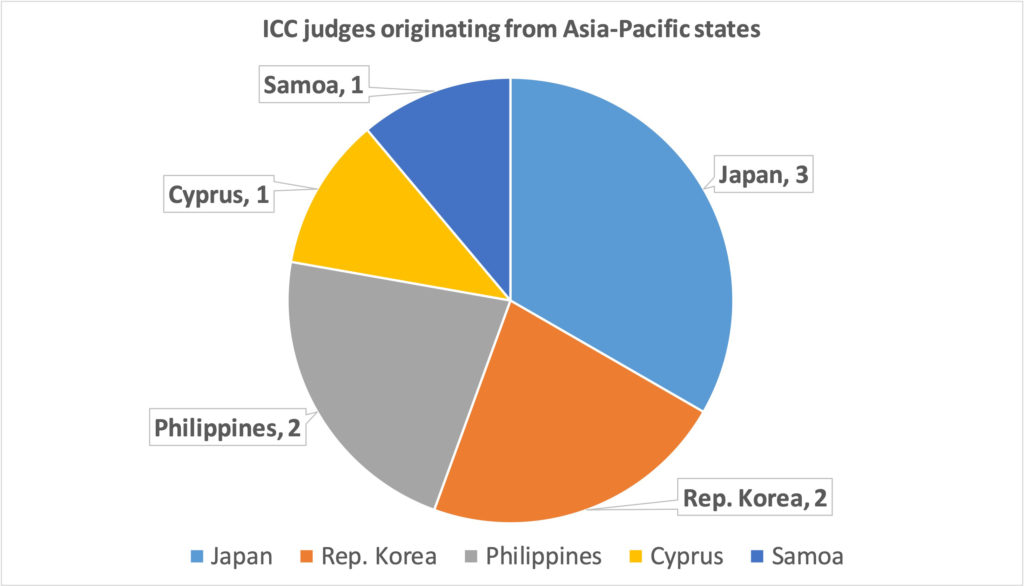

The concentration of nominations from only a few states is particularly noticeable in the Asia-Pacific region, which has been disproportionately represented by Japan, the Republic of Korea, and the Philippines, who have collectively provided seven out of the nine judges to have emanated from that region. On the flip side, only one of the seven nominating African states (Nigeria) has previously elected a judge, suggesting a welcome commitment to a more diverse African representation on the ICC bench. African states were not required to nominate any candidate under the 2020 MVRs.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Most states parties continue to lack a framework governing nomination of judicial candidates to the ICC. Many appear to select candidates in a largely ad hoc manner, absent publicizing available judicial vacancies, proper evaluation of candidates’ skills, and fair and transparent procedures. Many nominees were not evaluated by an independent, non-governmental body, which risks unwarranted political interference in the nomination process. Even a process that has the appearance of being open may not be in practice. A local NGO from one of the nominating states interviewed as part of our research claims that qualified candidates decided not to respond to their government’s open call for applications due to a perception that the process lacked independence and transparency, and the decision would be determined on political grounds in practice.

The concentration of ICC judicial appointments among a select group of states is concerning at a time when the court is increasingly taking on a more global character and moving into new situations and continents such as the Asia-Pacific and Eastern Europe regions.

A credible process for judicial nominations and elections is critical to ensuring a strong and legitimate judiciary. ICC judges have a key role to play in securing the institution’s long-term health: managing its proceedings well, authoring timely and authoritative jurisprudence, and providing an overall sense of mission and purpose. By enhancing their national nomination processes, states parties can take a step towards ensuring that the most qualified individuals serve on the ICC bench.

With a view to enhancing the quality of judicial nominees to the ICC, as well as the credibility of national nomination procedures, the Justice Initiative recommends states parties to the ICC take the following six actions:

- Acknowledge and promote international standards governing judicial appointments to the ICC. These standards have already been recognized by states parties in the discussions of the New York Working Group [pdf] and can be further enshrined in future ASP resolutions and national legislations. As mentioned in a previous post, these include: open and transparent procedures for nomination, including through public and open calls for candidates who may fulfil the criteria; clear, pre-established, merit-based criteria for the assessment of nominees; due regard for equitable gender representation; independent assessments of candidates by appropriate bodies, including government, judicial, and professional representatives; forwarding judicial posting announcements to relevant civil society organizations and groups to identify qualified candidates; engaging in consultation, as appropriate, with legal and academic institutions; and establishing and utilizing national panels of experts to assess and endorse candidates.

- Develop fair, transparent, and merit-based national-level nomination processes in accordance with international standards; and refrain from nominating candidates based on political or personal considerations;

- Engage the ASP to adopt guidelines on how ICC states parties can improve national nomination processes. The Council of Europe Committee of Ministers’ 2012 guidelines for nominating judicial candidates to the European Court of Human Rights offers an illustrative example.

- Enhance the role of civil society in the nomination and assessment of candidates, particularly as a means to collect information on candidates and to contribute to greater transparency in nominations procedures;

- Promote the study and practice of international criminal law in the context of domestic professional associations, academia, and civil society; and

- Refrain from the practice of vote-trading and toxic campaigning in ICC judicial elections.